7. Can We Try Something Different?Creative Communications Strategies

Politics and elections are serious business. Pushing for democratic progress often involves facing great risks, threats, and even dangers for your organization and – in some cases – your own personal safety. But just because the topics and consequences of your work are serious doesn’t mean they should be dense or dull.

Generally speaking, people don’t like to be lectured or reminded of how bad things are. People prefer to laugh and have fun. If you can use humor, entertainment, popular culture, or first-person experience as a way to deliver important and serious information, you’ll have a better chance of being listened to, and your audiences will be more likely to retain the information you are trying to impart.

Harness the Power of Art and Popular Culture

Popular culture is constantly teaching us what our society values and what our role in it is. Sometimes popular culture explicitly addresses politics, and sometimes it is more subtly commenting on the politics, ethics, and values we share or aspire to. But in addition to its ability to teach us, the real power of popular culture lies in the popular part. By definition, mass audiences are consuming it. If you can tap into pop culture narratives – and even better, if you can help shape them – then you will be communicating relevantly with broad audiences.

It’s really hard to inspire people to work for change when they can’t imagine what that change can look like or result in. Especially in closed societies and places where democracy is new, transitional, fragile, or a democratic tradition is new, people might not be able to adequately picture how their lives might change if their government were more accountable. Integrating popular culture strategies into your communications campaigns can be an effective way to show and teach your values in action or push back against common narratives that might harm or weaken your cause. Images, lyrics, and dialogues should be crafted to present improved circumstances that change could bring and not just concentrate on exposing present ills.

What is a Culture Campaign?

There are a number of ways to integrate pop culture strategies into your communications plan. Remember that popular culture in many instances is transnational, and you might be able to enlist figures outside your borders to assist your efforts, which is particularly important in closed societies.

- Praise or amplify positive narratives or trends you see in the arts or pop culture that reflect your messages.

- Correct or push back against negative or harmful narratives or trends in the arts or pop culture that undermine potentials for democratic progress.

- Work directly with artists, writers, actors, or other creators to help shape narratives that reinforce your frame and narrative during the production phase.

- Engage with your audience by drawing real-world connections to the art or culture they’re fans of or giving them ways to channel their passion into real-world action.

- Ask musicians to write songs for your campaign, filmmakers to produce short videos, actors to star in an ad or video, artists to create posters or grafiti, etc., for your campaign.

- Have celebrities join your campaign as spokespeople or trusted messengers, enlist them to amplify your messages through their performances and social media presence.

- Invite the public to post or submit popular culture contributions to your efforts.

As with your other strategies, any pop culture strategies and tactics you pursue should be in service to your larger goals. If you recruit a celebrity to be your spokesperson but that person is not popular with key audiences or isn’t willing to stay on message, then it’s not worth the effort. If, however, people are becoming increasingly cynical about democracy because the dominant television shows and movies all portray elections as rigged and politicians as corrupt, then you might want to work with artists and actors to create counter narratives that emphasize the benefits of participation and the importance of voting. Inviting the public to post or submit popular culture contributions to your campaigns can also help counter cynicism, while you will need to filter against trolls and other malign actors who may try to sabotage such efforts. This will reinforce your frame and lay a foundation that makes the rest of your work easier.

Your Turn: Politics and Popular Culture

Spend some time brainstorming the country’s most popular television shows, movies, books, music, and celebrities. Looking at this list, ask yourself the following questions:

For the narratives that reinforce your message and frame – especially the ones popular with your target audiences – how can you amplify and engage with those parts of pop culture? Can you tie your work and message to the pop culture modalities? Can you engage authentically with fans about the real-world counterparts or impact? Can you recruit the stars or spokespeople to join your campaign or collaborate with you in some way?

For the narratives that contradict or devalue your message and frame, think about how you can present counter narratives or rebuttals to what is harmful. Can you work directly with the creators to change how your issues are presented within the culture? Can you recruit the actors or artists involved to serve as spokespeople for your cause to debunk some of the harmful messages in their work? Can you parody or play with the original narrative to present your side or ideas instead?

Tips for Collaborating with Artists and Fans

Working in politics or for an NGO means you may have limited exposure to artists and other creative people. Here are tips for productive and mutually beneficial relationships with them:

- Let the artists do the art. An artist’s job is to be professionally creative, and you should give them the space to do so. Don’t try to tell them how to do their jobs. Let them pitch ideas of how their talents might be best used. If an idea sounds weird or out there at first, hear them out – just because it feels uncomfortable or different from how you have done things before doesn’t mean it is a bad idea. Don’t try to rein them in or change their vision unless absolutely necessary.

- An artist’s time is valuable. Artists and other creatives are paid professionals; don’t assume they will volunteer their services. Be prepared to offer and pay them at their market rate. If you can’t afford to pay them, ask them if they will volunteer their services or offer a reduced rate but understand this is a lot to ask for and treat their time with value and respect even if you are not paying for it directly.

- Collaborate, don’t dictate. You’re each bringing different knowledge bases to the table. Form a collaborative partnership where you’re lifting up each other’s work, not trying to make it fit into your preconceived ideas.

Sometimes your plan might involve outreach and organizing to fan communities. Fan communities are self-organized groups of people who love a movie, book, comic book, TV show, artist, musician, sports team, etc. Fan communities most frequently gather online around certain platforms or hashtags, but they also gather in person to enjoy performances, matches, or conventions. Fan communities often generate their own customs, language, and norms. One example is when Black Panther (a popular superhero movie which takes place in the mythical African nation of Wakanda) fans organized a “Wakanda The Vote” campaign to register people attending Black Panther film screenings to vote. The idea was not just to watch a screening about a fictional country built on the power of black people, but to simultaneously build black power in the real world.

If you plan to communicate with fan communities, here are some practical tips to keep in mind:

«««< HEAD:_guide/7-can-we-try-something-different-creative-communications-strategies.en.md

- Be a fan. If you want to talk to fan communities about a movie, TV show, book, or musician, be a fan! Fans are fiercely loyal and passionate about the object of their adoration – don’t start by criticizing or pointing out the shortcomings, but approach from a place of authentic admiration.

- Listen. Spend some time listening to the fans, how they interact, what their internal references and jokes are, and what they love about the thing they’re a fan of. It’s okay to lurk online or at events for a while, just listening to get a sense for the tone and topics to use once you’re ready to engage.

# Have authentic interactions. Don’t always try to wedge in your talking points or web address. Interact authentically and have real conversations with fans – pivot to your message when it feels natural.

- Be a fan. If you want to talk to fan communities about a movie, TV show, book, or musician, be a fan! Fans are fiercely loyal and passionate about the object of their adoration – don’t start by criticizing or pointing out the shortcomings, but approach from a place of authentic admiration.

-

Listen. Spend some time listening to the fans, how they interact, what their internal references and jokes are, and what they love about the thing they’re a fan of. It’s okay to lurk online or at events for a while, just listening to get a sense for the tone and topics to use once you’re ready to engage.

Begin adding French language & RTL CSS:_guide/7-can-we-try-something-different-creative-communications-strategies.fr.md

The Power of Comedy

This section is largely based on the work and findings of Caty Borum Chattoo’s research and report The Laughter Effect.

Using humor and comedy in your communications can help your message break through and stick – even when the issues themselves aren’t lighthearted or humorous.

There are a couple of messaging pitfalls that comedy can help overcome: messages that are over-complicated, and messages that are dire or hopeless. Sometimes democracy issues can be hard to understand and the details are often very specialized and technical – for example, the importance of reforming an electoral code. It might make the difference between credible elections or not – but once you start talking about the legal framework, people may get bored and stop listening to you. There is also the danger that, especially in closing spaces, the situations you are addressing feel dire and hopeless – there is nothing but bad news. When people feel hopeless they are again likely to stop listening to you. They don’t want to be reminded that things are bad, and the path forward is arduous.

The power of comedy is in humanizing issues and generating positive emotions about something that might otherwise seem dull, overly complicated, or hopeless.

Research shows that people take seriously the information they learn through comedy. By introducing a topic and information through humor, people’s minds are more open and ready to absorb otherwise challenging or complicated information. Comedians are often trusted messengers because they are seen as telling the truth or poking fun at power structures. This makes comedy an effective strategy for getting people to learn, care about, and take action on issues that might otherwise seem overly complicated, dull, or pessimistic.

There are, of course, times when a light-hearted or humorous approach is inappropriate. But this approach is overlooked often and is so effective that it should at least be considered and integrated when appropriate.

The Format of Your Comedy Matters

There are a number of ways to introduce humor into your communications, and each serves a different purpose and conveys different cues about your message. It’s not enough to decide you want to integrate humor into your messaging – think carefully about what kind of humor is appropriate for the context and best serves your purposes.

- Satirical news. Satirical news points out and reframes absurdity. For it to work, your audience must have some basic familiarity with the situation being satirized, or they will not understand it or find it funny. Satire is good for motivating the base of people who already agree with you, but is likely to alienate or turn off people who don’t agree with you.

- Scripted, comedic storytelling. Funny scripted stories – TV shows, public service announcements (PSAs), movies, online videos, etc. – are great for creating relationships between the viewers and your characters. This understanding or empathy can help normalize unfamiliar experiences and expose the viewer to people or situations they might not otherwise encounter.

- Humorous ads. Making someone laugh in a short amount of time captures their attention and sticks in their memory. Humorous ads – print, online, televised, or radio – work to quickly grab your attention and can be very memorable. They can also spark discussion and sharing with friends and family.

- Stand up comedy and sketch comedy. This form of comedy can introduce longer topics, help people critically evaluate them, and break taboos.

Comedy works best when people like or trust the comedian. Choose your messenger wisely for maximum impact. Your comedy should also be funny (this sounds obvious but is surprisingly hard to do). Partnering with a professional or experienced comedian can help you be sure you’re funny and therefore successful.

How Comedy Works

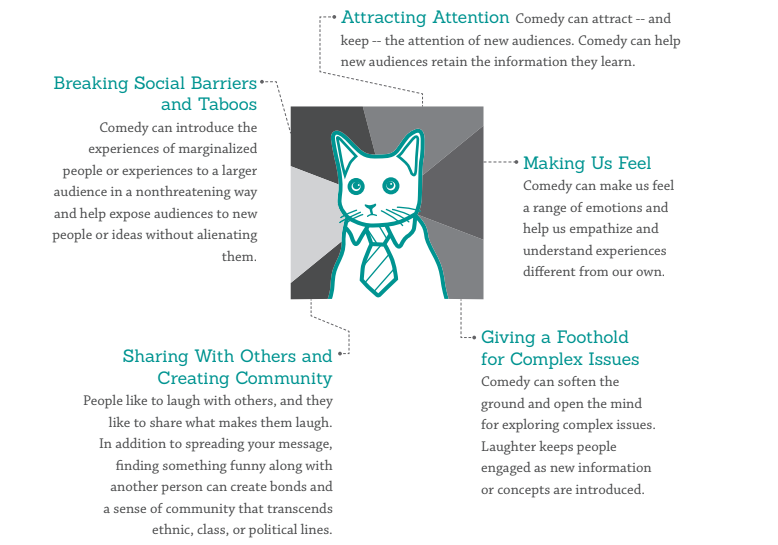

There are five main ways comedy works to influence your audience:

YOUR TURN: Topline Messages

Look back at your topline and related messages in your communications plan. Are there any messages or concepts that are difficult to explain, overly complicated, dull, or very dire and hopeless?

If so, brainstorm ways humor might help you better convey those messages. Here are some questions to get you started:

Experiential Learning and Communications

Experiential learning is the process of experiencing something new and then reflecting on that experience to come to new knowledge or larger lessons. It is commonly used in the classroom or in job training programs, and used creatively, the same principles can be applied to a communications campaign.

In some cases, your audience will undergo a new experience themselves, and you can help enrich the reflection stage of the experience so they learn new lessons. For example, if people are showing up at the polls and there is only one candidate on the ballot (or only one viable candidate), they may vote for that one candidate (the experience) and not think much of it because there’s only ever been one candidate on the ballot (no reflection). Instead, you can aim your communications to interact with that voter shortly before or after their experience voting to add context and encourage reflection on their experience. Why was there only one candidate on the ballot? Can you have a credible election without choice? How would the country be different with a real choice at the ballot?

This type of communication can occur on any of the platforms or formats already discussed. For example, you might host a Facebook Live shortly after the election in which you pose questions to the audience aimed at causing reflection and ask them to contribute their thoughts and reactions about their experience in registering to vote. You could run newspaper or digital ads aimed at provoking reflections on common experiences that the audiences had while voting. You could hold community forums or go canvassing door-to-door to hold in-depth conversations in which people share their experience over the course of the election period and, through guided discussion, reflect on that experience to learn larger lessons about democracy, credible elections or accountability in government.

In other cases, your audience may not undergo the experience themselves, and so you’ll want to simulate it for them or otherwise create some kind of empathic connection to the experience. For example, you could create a simple first person, role-playing game that puts the user in the position of having to vote with a physical disability. At each barrier in the process, the player would have to decide what to do or how to handle it. If there are stairs to the entrance of the polling place, players would have the option of asking others to carry them up the stairs or not voting that day and going home instead. By forcing able-bodied players to make choices from the point of view of a disabled voter, the player will reflect on the importance of accessible polling places, something they may not have given much thought to in the past.

You can achieve a similar outcome with videos, virtual reality, slide decks, online quizzes, or first person essays aimed at putting the audience through an experience different from their own. Be sure to structure it in such a way that there is room for reflection about the experience to increase the chance of the audience retaining what it learns.

For either of these approaches, it’s best to have immediate actions ready for someone to take, in order to channel their newfound knowledge and enthusiasm into useful action. This might mean something as simple as signing up for your email list for updates and alerts, or something more involved like protesting inaccessible polling places at the election commission – but you want to be sure people take action based on what they’ve just experienced and learned.

YOUR TURN: Audience Experiences

Are there experiences that your audiences will have or should have that can teach valuable lessons about your work and mission? Brainstorm what those experiences could be:

Now for each experience, decide whether your audience is likely to experience it themselves, or will need it simulated for them in some way.

If they’ll experience it themselves, how will you encourage them to reflect and act from the experience? If they will not experience it for themselves, what are effective ways to simulate the experience and encourage them to reflect on it?

Sharing People’s Stories

As already discussed, using narrative is a powerful way to emotionally connect with your audience and relay the story of your work, organization, or findings. For the most part, the narrative approaches in Chapter IV are for stories that you created or sought out – and thereby maintain careful control of the narrative.

As a related strategy, it can be very compelling to hear from different people about a range of personal experiences or stories. Collecting and curating user-generated videos or stories can show the diversity of experiences and ideas about different issues, increasing the chances that the audience will connect with one of them, and also learn to experience and empathize with different people and points of view.

This strategy can be difficult to carry out for a number of reasons. People must have an interesting or compelling story to tell. They need to feel safe – emotionally and physically – sharing it with you. They need to feel comfortable with the technical aspects of submitting their story (if it requires special equipment, internet bandwidth, etc.). And finally you need to have the staff capacity to vet and curate the stories as they come in – while you want to show a range of experiences and emotions, you still want the stories to fall within your frame and reinforce your message, and at the very least not contribute to hate speech or abuse.

But if you can overcome those challenges, the benefits can be great. People love to tell and listen to stories. Showing a range of personal stories can create empathy, understanding, and engagement that data, messaging, and talking points never will. This strategy also gives regular people a way to get involved and feel like their story and experiences are part of a larger community. Learning you are not alone in how you think or what you’ve experienced creates a powerful form of community that will strengthen people’s commitment to your work and cause.

You might consider this strategy when you think a range of stories will reinforce your overall message and frame, or when a behavior or outcome would benefit from being reinforced by a person’s peer group. For example, perhaps you are trying to boost voter turnout with young women or men ages 18-25. If they aren’t voting because they don’t perceive it as cool or worth their time, then videos, statements, and infographics from an election observation group might not be enough to convince them. However, if they can explore 100 videos of other young women men telling their personal stories of the first time they voted and how it made them feel, your audience is more likely to trust those authentic narratives. They’ll want to belong to a community that votes, like those in the videos.

In some instances, you may want to recruit and collect the stories yourself. This is a good approach to take if you want them all to look similar aesthetically (you can control how they’re filmed), or you want to solicit stories from specific people and you want to make it easy on them. The drawbacks to this approach are that you’ll need enough staff time and skills to recruit the people, film or otherwise collect their story, and then edit or produce the final narrative.

Instead, you might opt to have users submit their own stories. This will result in a wider variety of stories and experiences, but they will vary in quality and you will still need staff time to ensure that the stories you display help your mission.

However you decide to solicit and collect people’s stories, you’ll need to think about how you plan to display them, how people will find them, and what you hope they’ll do once they hear the stories. You may also need to include some kind of legal disclaimer about how and who can publish or share stories, and how they can be used.